P14 Weekly Screen #7 - Brazil

Why Brazil + a targeted watchlist of 5 stocks, each with a mini-thesis

Greetings.

It should come as little surprise that emerging market equities have performed well this year with the “debasement trade” in full swing. Brazil, as the largest Latin American economy and one of the most liquid EM markets, has been a primary beneficiary, with the Bovespa Index up ~30% YTD. Yet despite this headline performance, Brazilian equities continue to trade at a material valuation discount, with the Bovespa at ~9x NTM P/E vs. ~13x for broader EM.

Over the past 10 years, equity investors would have made more money invested in Brazilian equities (in nominal terms), with the Bovespa returning 258% vs. 230% for the S&P 500. The promise of the Brazilian market has faltered in recent years. Brazil has repeatedly been deemed “uninvestable,” as companies and investors have had to contend with political instability, inflationary pressure, and restrictive monetary policy. Since 2021, the Bovespa has returned just 34%, compared to 83% for the SPY.

I believe Brazilian equities are positioned to deliver superior returns over the next few years relative to the S&P 500, with the valuation gap vs. other emerging markets set to narrow. In my view, Brazil is approaching an inflection point where the macro stars are beginning to align, with the debasement trade continuing alongside monetary easing and political optionality, setting the stage for incremental foreign inflows, a recovering consumer as borrowing costs fall, and upside from a more pro-business outcome if the right wins in 2026.

Are positive returns set to continue? Are the skies clear heading into 2026, and is the debasement trade the only thing Brazil has going for it? This is what will be covered in our broad LONG Brazil thesis (free). After that, P14 will provide a targeted list of 5 stocks, each with a mini single-stock thesis, that I believe are best positioned to benefit from the overarching theme (paywalled).

But first, let us start with the building blocks.

What drives the Brazilian economy

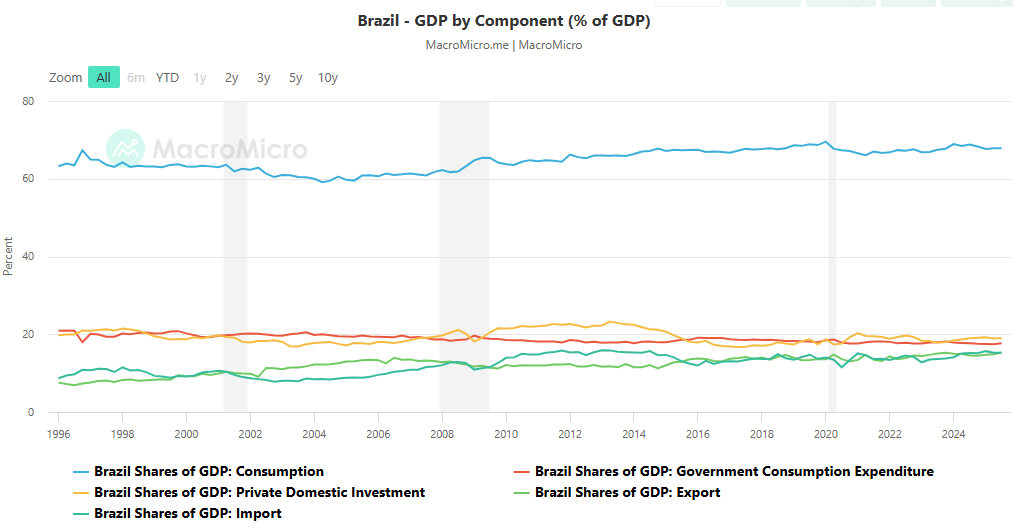

It is often a misconception that Brazil is an export-driven economy. Naturally, a declining dollar is perceived to benefit commodity currencies the most, and Brazil is often grouped with export-oriented economies. While exports are an important component, with Brazil being a resource-rich country, the economy is fundamentally domestically driven, anchored by a large services sector, alongside a globally important commodity and agribusiness complex. Services consistently account for ~60–70% of total GDP and employ over 70% of the workforce.

In 3Q25, the economy generated an estimated ~$552B in real GDP, up +0.1% Q/Q vs. +0.2% estimates, and +1.8% Y/Y. This marked the 5th consecutive real GDP growth slowdown since growth began decelerating post 3Q24. The primary driver continues to be a persistently restrictive monetary policy.

Brazil is a consumption-driven economy, with consumption accounting for 67.82% of GDP. While its share of real GDP has remained in the 60s since 1996, consumption’s contribution to growth has weakened materially since real GDP growth began decelerating post 3Q24. In 3Q25, consumption contributed 0.24pp to 1.82% Y/Y GDP growth, compared to a 1.22pp contribution to 2Q25’s +2.36% Y/Y growth. Consumption growth has decelerated from +5.83% Y/Y in 3Q24 to just +0.36% Y/Y in 3Q25.

Domestic demand is clearly moderating. Despite the unemployment rate sitting at a historically low 5.4% and real wages continuing to grow, albeit at a slower Q/Q pace, consumers are increasingly feeling the strain from an elevated cost of debt.

With the exception of a surprise upside print in October 2025, retail sales continue to exhibit a decelerating trend, with weakness most evident in big-ticket purchases, reinforcing that the cost of credit is the primary constraint.

The investment component of GDP, or private domestic investment, has hovered around the 18–19% range post-COVID. Its share of GDP rose in 3Q25 to 19.06%, compared to 18.95% in 3Q24, primarily due to the deceleration in consumption rather than an acceleration in investment. Like consumption, private domestic investment has slowed meaningfully, decelerating from +7.3% Y/Y in 3Q24 to +2.4% Y/Y in 3Q25. Many CEOs remain in wait-and-see mode as they grapple with a persistently high cost of debt.

Government spending, unlike other demand-side drivers, has accelerated in 2025, constituting 17.66% of real GDP in 3Q25, up from 17.46% in 2Q25, growing +2.1% Y/Y. Under the socialist regime, spending has increasingly been directed toward social programs rather than fiscal investment, with the acceleration in 3Q25 primarily driven by Bolsa Família, public services expansion, and spending ramping up ahead of municipal elections. Spending on social benefit programs for the elderly and low-income people with disabilities increased nearly 10% between January and October, according to Treasury data. Pension outlays, which already represent the largest share of public spending, grew +4% over the same period.

Net exports were the key factor that kept the Brazilian economy from contracting in 3Q25. Despite tariffs, export growth continued, rising +4.6% Y/Y, compared to +1.1% Y/Y in 3Q24. Much of 3Q25’s growth was driven by September’s +7.2% Y/Y with exports to China offsetting the tariff-driven decline to the US. Since August, exports to the U.S. have fallen 25.1%, while exports to China grew 28.6% vs. the same period in 2024. Looking ahead, the new U.S.–China soybean deal introduces downside risk, as soybeans represent ~15% of Brazil’s total exports, with ~80% destined for China. In aggregate, exports account for 15.3% of Brazil’s real GDP.

Imports paint a picture of a polarized economy where industrial re-stocking has decoupled from household demand; total imports grew +8.2% Y/Y in 3Q25, a significant rebound from the -0.7% Y/Y contraction seen in 3Q24. This growth is primarily fueled by a +26.7% Y/Y surge in Capital Goods—bolstered by high-value infrastructure imports like a $2.4 billion oil platform in September—and a +9.4% Y/Y increase in Intermediate Goods required for the country’s industrial base. Conversely, Consumer Goods imports have decelerated to +4.0% Y/Y, reflecting a fatigue in domestic purchasing power under a 15% Selic rate.

To protect the 2026 primary surplus goal of R$ 34.5 billion (0.25% of GDP) against mandatory expenditures that are consistently hitting the fiscal framework’s 2.5% growth ceiling, the Finance Ministry is now considering an increase in Import Taxes. This regulatory lever, which bypasses Congressional approval, aims to secure an additional R$ 14 billion in 2026 revenue to offset government spending as the country heads into the election cycle. Imports make up 15.2% of Brazil’s real GDP.

Despite recent demand-side weakness, the Central Bank of Brazil has raised its economic growth forecasts in its latest quarterly report. The authority now projects +2.3% Y/Y GDP growth for 2025 (up from the +2.0% forecast in September) and a slight increase to +1.6% Y/Y for 2026 (up from +1.5%).

Monetary policy and Inflation

It should come as no surprise that the cost of debt remains the primary bottleneck to a recovering consumer and, by extension, a headwind for equities.

Consumer credit is under significant strain as borrowing costs remain elevated. While total credit volumes are still technically expanding, the quality of that credit is deteriorating rapidly. Household debt-to-GDP stands at a record 36.6%, while default rates reached 4.0% in October 2025, the highest level since 2011. In 3Q25, interest rates on revolving credit cards were at a staggering 441.4% annually. On average, Brazilians are allocating 29.3% of monthly income toward servicing debt, including interest and principal.

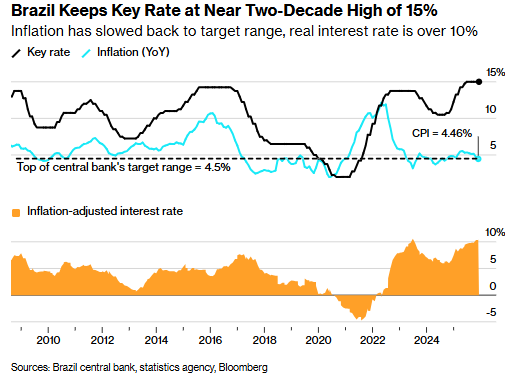

One of the key drivers of EM equity performance in 2025 was monetary easing, as mid-year expectations for Fed cuts supported risk assets returns. The majority of countries within the MSCI EM Index delivered rate cuts during the year. Brazil moved in the opposite direction. Since its hiking cycle began in September 2024, the BCB has raised the Selic rate by 450bps, with 275bps implemented in 2025 alone.

Brazil now has one of the highest real interest rates in the world. One could argue the BCB has overcorrected in response to inflation, reflecting PTSD from the post-COVID inflation peak near 12% in 2022. More recently, inflation rose to ~5.5% before easing. Brazil’s formal inflation target is 3%, with a ±1.5pp tolerance band. The November CPI reading of 4.46% brought inflation back within the BCB’s target range for the first time in 14 months. Despite this, the BCB maintained a cautious stance at its 12/10 meeting, holding rates unchanged and offering no explicit forward guidance.

Consensus interpretation of the COPOM minutes reflects policymakers seeking more time and more data before initiating an easing cycle. Analysts who previously expected a January cut have now pushed expectations toward March.

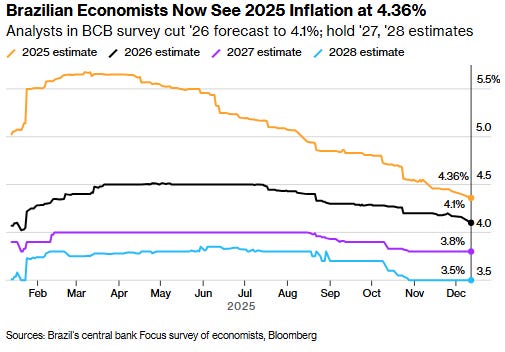

Nevertheless, a monetary easing cycle is coming, and the decline in real rates is the crux of the long Brazil thesis. Cuts may not begin in January, as reflected in recent BRL weakness, but inflation expectations continue to ease, with economists revising forecasts lower.

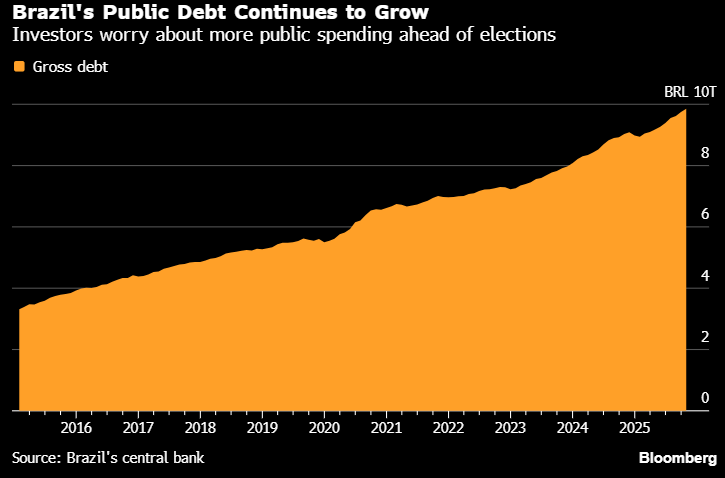

Beyond slowing demand, a major reason easing is inevitable is Brazil’s rising debt-to-GDP ratio. With ~15% nominal interest rates, a substantial portion of the federal budget is diverted toward debt servicing, limiting productive investment. Since the current administration took office, government spending has increased ~20%, while debt-to-GDP has risen more than 10pp to ~80%, one of the highest levels across EM. While elevated rates have helped contain inflation, maintaining a 2-decade-high Selic is unsustainable given the trajectory of public debt.

Politics

No discussion of Brazil is complete without acknowledging its volatile political environment.

The current Lula administration began in January 2023 and is set to end on December 31, 2026. Lula is 80 years old and plans to seek re-election in late 2026, which would mark his 4th term. Before assessing how politics feed into the Brazil thesis, it is important to review how Brazil has performed under the 3 Lula terms.

Term 1: 2003–2006

The Bovespa rose ~300% in BRL terms. The Lula transition proved more market-friendly than feared, leading to a significant re-rating of Brazilian assets as the country moved toward investment-grade status. Real GDP growth averaged ~3.5% annually, coinciding with the early stages of the China-led commodity boom.

Term 2: 2007–2010

The Bovespa rose ~56% in BRL terms, with returns tempered by the 2008 crash and followed by a V-shaped recovery. This period was marked by IPO fever and the discovery of Pre-Salt oil reserves, which propelled Petrobras and Vale into global prominence. Real GDP growth averaged ~4.7% annually, with only a brief recession of -0.1% Y/Y in 2009. Lula left office with 7.5% Y/Y GDP growth in 2010, the strongest in decades. Brazil entered the GFC with ~$200B in reserves and a banking system with no subprime exposure, enabling one of the fastest recoveries globally.

Term 3: 2023–present

The Bovespa has risen ~44% in BRL terms. 2024 delivered a -10.4% return as markets grappled with high interest rates and fiscal concerns. 2025 has seen a strong rebound driven by foreign inflows and the debasement trade, despite the Selic reaching 2-decade highs. Real GDP growth has averaged ~3%, assuming the +2.3% 2025 estimate holds, with growth slowing in 2025 due to high real rates.

What Lula’s economic record tells me is that he is not as bad as the consensus paints him to be. It is easy to get dragged into the camp that right-wing, conservative leadership equals pro-business and therefore great for stocks, but Lula’s 3 terms suggest a more nuanced reality. His track record has been better for growth and Brazilian assets than most want to admit, dare I say.

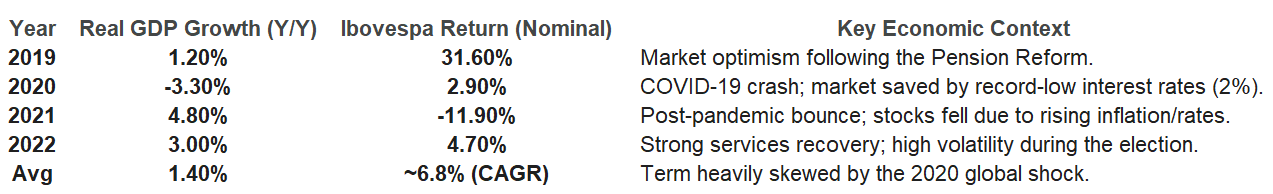

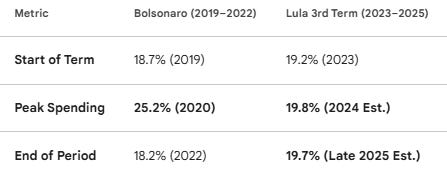

In fact, compared to the 3 presidents who served between Lula’s 2nd and 3rd terms, Lula’s Brazil has materially outpaced all 3 on average GDP growth. Rousseff (2011–2016), left-wing, averaged -0.5% GDP growth. Temer (2016–2018), centrist, averaged +1.3%. Bolsonaro (2019–2022), right-wing, averaged ~+1.4%, though Bolsonaro’s term was heavily muddled by COVID.

Ironically, toward the end of his term, the right-wing Bolsonaro administration was spending at levels typically associated with socialist governments. He declared a “state of emergency” to bypass the law that prohibits new social benefits during an election year. The monthly payment for Brazil’s main welfare program was hiked by 50%, and the number of families receiving aid was expanded to over 20M, a meaningful jump clearly intended to capture the lower-income vote, among other measures. It is true, however, that government spending growth was slightly lower during Bolsonaro’s term, excluding the COVID period.

Of course, these efforts were in vain. Jair Bolsonaro became the first sitting president in Brazilian history to fail in a re-election bid. His loss to Lula in 2022 was decided by the narrowest margin in the country’s democratic history, 50.9% to 49.1%, a difference of roughly 2.1M votes out of nearly 120M cast. The primary drivers of his loss were COVID mismanagement, inflation that translated into an extremely high cost of debt, and the center’s rejection of radicalism, driven in part by his continuous attacks on institutions.

In my view, the market fears Lula too much and is desperately searching for its right-wing or centrist, fiscally responsible savior. There is legitimate cause for concern regarding belligerent social spending coupled with a rising Debt-to-GDP ratio, which has contributed to weak growth and underinvestment in a market that remains more cyclical than is ideal.

That brings me to the major catalyst the market is so obsessed with: the elections.

In October 2026, Brazil will hold elections for the President, all 27 Governors, the entire Lower House, and two-thirds of the Senate. These elections have the potential to realign macro policy, allowing Brazil to evolve into a more fundamental market rather than a trading one.

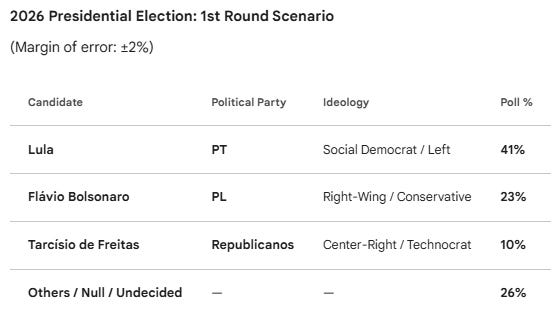

On the left, the clear leader is Lula, who is seeking his 4th term and would be 81 at the time. Lula lost popularity earlier but regained ground following tariff disputes with the U.S., repositioning himself as a defender of national sovereignty. U.S.–Brazil relations are now thawing, with agricultural tariffs being rolled back. Lula continues to cement his position, particularly after Jair Bolsonaro’s conviction and 8-year ban from office.

On the opposition side, the picture is far more divided. A key driver of recent downside in Brazilian equities has been Jair Bolsonaro’s endorsement of his son, Flávio Bolsonaro, which caught the market off guard, as the right’s early favorite had been São Paulo Governor Tarcísio de Freitas.

Bolsonaro’s endorsement of his own son signals he is trying to preserve his chance of getting out of prison. As noted, Bolsonaro is ineligible for public office, including the Presidency of the Republic, so he must ultimately hope his chosen candidate wins the presidential election to maintain his political capital. More recently, the Senate approved the Dosimetry bill, which would reduce Bolsonaro’s 27-year sentence to 2.3 years. Lula will likely veto the bill, but because it passed with a strong majority, many analysts believe Congress may have the votes to override the veto in early 2026. Justice Alexandre de Moraes has already called the bill a “farce” and a “disrespect to the court.” Even if Congress overrides the veto, the Supreme Court is expected to challenge the law’s constitutionality, potentially striking it down.

If Brazil gets another Lula term, Bolsonaro is more likely to remain locked up for a long time. What is also notable is the parallel with Lula in 2018, when he was imprisoned during Operation Car Wash (Lava Jato) after being convicted on charges of passive corruption and money laundering. Lula ultimately transferred his support to Fernando Haddad, the former Mayor of São Paulo. The appointment of a loyalist, in the sense that Lula is Haddad and Haddad is Lula, later paid off when Lula won and appointed Haddad as Finance Minister.

Fast-forward to today. Haddad has recently stepped down, stating that he wants to be the primary coordinator for Lula’s 2026 re-election campaign. Under Brazilian law, serving as Finance Minister while leading a national campaign is considered a conflict of interest.

All in all, the case for an opposition win has become messy. In the P14 view, we are likely to see the right consolidate under a single candidate as the election year progresses, especially into the second round, where Flávio, Tarcísio, and Caiado can unite.

As it stands today, Lula is comfortably in the lead. The most recent polling for the October 2026 election from the Genial/Quaest survey, released earlier this week, reflects that.

The path forward

At its core, investing in Brazil over the next few years is a monetary easing play. As one of the few EMs that hiked in 2025, the path toward lower rates is clearer than ever.

In 2021, Brazil passed a landmark law granting the BCB formal operational autonomy, the culmination of decades of attempts to shield monetary policy from political cycles. 2026 will test this framework, and political pressure is mounting. Lula continues to suggest he can “smell” interest rate cuts coming. He has expressed “full confidence” in Galípolo, while also hoping the Governor is “breathing the same air” as the rest of the country. Galípolo, despite being Lula’s former appointee, has acted more aggressively than expected to demonstrate he is not a political puppet.

There are two sides to this coin. If Galípolo bows to political pressure and cuts rates before sufficient fiscal reforms are passed, the BRL could face a sharp selloff. Investors fear that a politically motivated cut would signal a breakdown in BCB independence, leading to capital flight and a de-anchoring of inflation expectations, which would ultimately require even higher rates down the line.

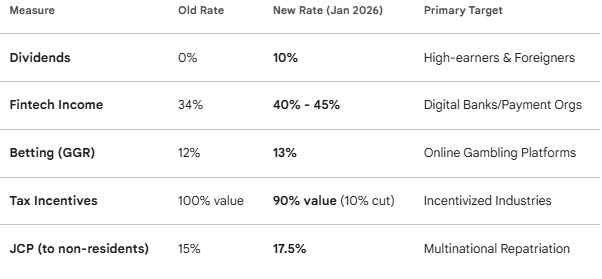

The good news is that the data supports a cut. In 1Q26, exports are likely to face pressure from the U.S.–China soybean deal. The demand side is cooling as demand-driven inflation fades and consumer credit freezes. Fiscal reforms aimed at increasing tax revenues have been passed, and this is some evidence of the “fiscal effort” the BCB has repeatedly stated it needs to see before beginning an easing cycle.

In the P14 view, the October 2026 election adds meaningful optionality to the thesis. I believe the market fears Lula too much, although there is valid reason for concern at present. Volatility driven by the election news cycle should be bought, as monetary easing is coming regardless. The cost of credit itself is likely to play a decisive role in the election outcome, increasing political pressure on the BCB. If rate cuts fall meaningfully short of consensus expectations of 350–400bps, there is additional optionality in the form of a right-wing victory.

Ultimately, in the P14 view, the dollar debasement trade is set to continue. Combined with monetary easing and political optionality, Brazilian equities are positioned to re-rate above their ~9x NTM P/E, supported by increasing foreign capital inflows, a recovering consumer driven by lower borrowing costs, and the upside scenario of a more pro-business equity market in the event of a right-wing win.

Now for the most important part.

Here are 5 Brazilian stocks, each with a mini-thesis, that I believe are set to re-rate in 2026.